So, You Just Bought a Telescope

I recently started to write an article on the basics of buying your first telescope; what to look for, model recommendations, things like that, but I quickly realized there wasn’t much new to add to the topic that was not already present in the dozens of other online articles. I also started writing it in the first week of December which may have been a little late as far as desperate Christmas shoppers are concerned. However, I have yet to see many articles on the topic of what you need to buy with your shiny new telescope.

A telescope is only part of your astronomy experience, which for someone new to astronomy may be a surprise. Astronomers online have discussed the idea of “What is the best first telescope?” to death (the answer is a 6” or 8” Dobsonian, by the way) but not much attention seems to be directed towards other necessary items to enrich your journey into exploring the night sky. Not all of these are needed, and only some are recommended depending on your setup.

A Few Eyepieces & a Barlow

On average a telescope includes less than 1 eyepiece. Starter scopes may come with 1, but either way you will be limited to one magnification which can reduce your observation of night sky objects of varying apparent size. The Andromeda Galaxy, for example, spans 50 times the width of the Ring Nebula from our perspective.

The big question then is which eyepieces and how many? First, some math:

Magnification = (Telescope Focal Length) / (Eyepiece Focal Length)

For example, my Celestron C8, a 2000mm focal length telescope, came with a 25mm eyepiece which is equivalent to 80x magnification because 2000 / 25 = 80

You should aim for having enough eyepieces to provide a decent variety of magnifications, though the exact number is up to you. The maximum magnification should generally be no more than twice the telescope aperture (diameter) in millimeters (so a 100mm telescope will probably perform poorly above 200x). Again referring to my C8, which has an aperture of 200mm, I would not recommend observing using magnifications approaching 400x.

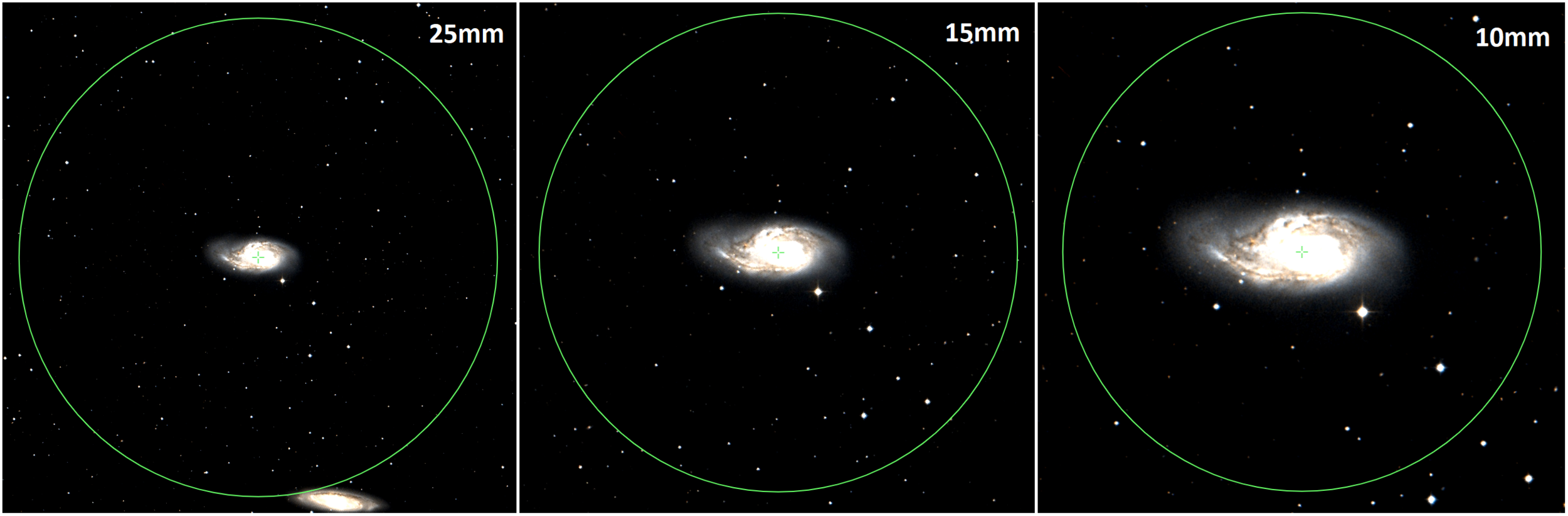

M66 as seen through various eyepieces in my 2000mm C8 telescope

Again then, how many? In my opinion you don’t need more than 2 or 3 when starting out, but the best choices will depend on your telescope’s size and focal length. 25mm eyepieces are commonly included in starter telescopes and adding a 15mm along with a ~10 or 12mm would generally be a good selection. If you bought a Dobsonian like the Orion XT8, which has a focal length of 1200mm, these eyepieces would provide magnifications of 48X (25mm), 80X (15mm)and 120X (10mm).

But wait! The Orion XT8, which has a 200mm aperture, would surely allow for magnifications closer to 400x, right? That is correct, but I’m trying to be financially conservative here. Instead of buying increasingly tinier eyepieces, we can use something called a Barlow Lens.

Barlow Lenses add a modifier to the magnification of the eyepiece. One of the most common type of Barlow lenses doubles the effective focal length of whatever eyepiece is inserted behind it. This means that 10mm eyepiece, which by itself produces a 120x magnification, with a barlow now shows 240x. Include a 2x Barlow with the eyepieces listed above and your shiny new Orion XT8 would now produce views at 48X, 80X, 96X, 120X, 160X, and 240X.

A Celestron 2x Barlow usually runs under $40

There is a catch to this - the Barlow works by effectively “cropping in” on the field of view on the telescope, so the view will be somewhat darker since you are in effect using a smaller aperture. For some objects (like the Moon) this will be almost unnoticeable, but if you are chasing a closeup of a dim and distant galaxy, you may find that using a barlow does not help your pursuit.

Filters

Filters cut out unhelpful bandwidths or intensities of light which can make visual observation difficult. I won’t spend too much time on these since I spend most my time photographing rather than looking so to be quite honest my experience on them is limited. Some primarily visual astronomers swear by them though, so there are two main types which may be helpful:

- Reduction filters (or Moon filters). These are little sunglasses for your eyepiece so you don’t give your pupils a muscle strain when they look a bright Moon. Looking at the Full Moon through a telescope isn’t harmful in any way (aside from the fact that its a waste of time, in my opinion), but it will definitely leave you with 0 night vision and probably seeing spots

- Color Filters: These can be helpful for enhancing certain planetary features. Red and Blur filters can especially bring out details on Mars and Jupiter. Planets are typically no higher than 45 degrees in Kansas skies so planetary observing (or photography, really) has never been my forte.

Special Case: Solar Filters

As with all other filters, solar filters reduce unwanted light bandwidths. The difference is that instead of simply enhancing observation, they also make sure you are not instantly blinded. Solar filters are cheaper than you may think, at least if you want to observe the sun in White Light.

Disclaimer: NEVER observe the sun through any optics without proper filtering in place on the front end of the telescope

A White Light solar filter allows almost any telescope to be quickly converted into a solar instrument capable of safely showing sunspot activity on the Sun’s photosphere (which can be thought of as the closest thing a hydrogen plasma ball can have to a surface). These typically work in 2 parts, first by cutting out harmful wavelengths like UV, and second by then heavily reducing the amount of remaining light which is allowed to pass through the filter until is is safe

An AstroZap White Light Baader filter

This White Light filter I have for my C8 cost about $80, but different brands and varying sizes of telescope will have their own prices.

One more note on filters: As of early 2020 when this article is going out we are barely headed out of a solar minimum. Solar activity is currently pretty minimal in white light, so waiting a few years until sunspot activity increases may be a decent idea. Unless you like staring at a blank white circle.

Sky Atlas

You now have all of the optics required to view the night sky, now what? You can explore random bits of sky on your own, but if your skies are somewhat light-polluted or your time outside is limited, this pursuit may end up in varying amounts of boredom or frustration. Fortunately, many astronomers through the past few hundred years have done the work for you!

A Sky Atlas will show you the locations of thousands of stars, nebula, and galaxies in all directions for both the northern and southern hemispheres. Not only will this enable you to quickly find the more interesting objects, but it will also help you learn the constellations and star names. Sky & Telescope’s Pocket Sky Atlas is a popular option (available via their online store), but others do exist.

For an honorable mention, the book Turn Left at Orion will also suffice for an early guide on the best and brightest objects to see. This book can be purchased from several online sources, or found on the Cambridge University website.

I recommend books first since staring at a computer screen does not usually bode well for night vision, even if that screen is red-filtered. Still, there are digital atlases available as well. In-the-sky.org is one such option, and it can also tell you when certain objects are in the best position for observation.

If you want an option to keep on your laptop (since internet access usually does not pair with places far away from light pollution), check out Sky Tools or Stellarium.

Sky Tools is is a virtual observation assistant which can show lists of targets by target type (clusters, double stars, etc) and give you useful information like their magnitude, size, altitude, as well as show you the star field around your target of choice based on custom input of the eyepieces and telescopes you have available. The downside is the cost; Sky Tools has a few different versions.

Stellarium, however, is completely free. This program is a virtual planetarium which can show you thousands of objects (and you can even add additional catalogs which interest you), allows custom framing based on available optics (so you can virtually test your new eyepiece before buying it!) , and can even display non-western constellations. Even without a telescope, this program is a lot of fun to use.

A Telrad

Many visual telescopes include wider-field optics for roughly lining up targets in different areas of sky. This may be a smaller telescope with a larger field of view or something as simple as a red dot projected onto a plastic lens. A Telrad is somewhere between these two.

A typical Telrad

Telrads project a target reticle onto a transparent plate, but each of the circles on this reticle indicate an angular distance of 0.5, 2, or 4 degrees. These have become popular enough that some night sky Atlases include a standard references to these distances on their pages.

Not everyone needs a Telrad. They are incredibly useful when paired with a Sky Atlas, but mostly for hand-driven telescopes like Dobsonians. If you have a motorized telescope with a hand control capable of automatically pointing at these night sky objects, then a Telrad may not be needed, but it can still be useful. The observatory at which I volunteer requires manual alignment on a bright star to verify its position during startup each evening, and we frequently use a Telrad to assist us in this task.

Like Photography? Start out with an Eyepiece Adapter for your Cell Phone

Modern smartphones are quickly becoming proficient in night sky imaging, with some even including a “night mode” camera function which essentially live-stacks images together for taking photos in the dark. With a little practice these can be lined up with an eyepiece to take basic photos through the telescope. You can hold your phone over the eyepiece, but doing this accurately enough to keep a fleeting planet in view, taking the picture, and possibly even adjusting the telescope at the same time can be a challenge.

Eyepiece adapters make this easier since they clamp onto the eyepiece on one end and secure a phone on the other. Most smartphones still will not take good photos of night sky nebula and such (as much as I can judge such a subjective quality), but for the planets and the Moon it should perform decently well.

I don’t use these much anymore, but for someone just starting their journey into astrophotography it is a cheap way to test the waters without spending the additional hundreds needed for a dedicated camera.

Celestron’s “NeXYZ” Adapter

What If I need more In-person instruction?

I admit this article is “geared” more towards “what to buy” rather than “how do I use my telescope?” but this kind of thing can be difficult to teach at a distance. That being said, if you have a question about your specific telescope, feel free to reach out to me using the Contact page or to the local Astronomy Club in your city (if it has one).

Speaking of Astronomy Clubs, for Wichita-area residents you could also contact the Kansas Astronomical Observers. Our meetings from May-September occur at 7:30pm on the third Saturday evening of each month at the Lake Afton Observatory. Any astronomer there would be happy to try and help you learn how to use your telescope or point you towards the more interesting seasonal night sky objects.

Where can I buy any of this?

I haven’t included too many links in this article since web pages change often enough to worry about broken links, but I have found almost everything I need regarding astronomy from these websites:

For a final thought, just remember you don’t necessarily need all of this (or perhaps any of it). For someone with a small tabletop telescope, a single eyepiece may be enough to satisfy your fix for gazing upwards. If you are a semi-retired male in his 60’s looking to spend money on something other than model trains, maybe money isn’t an issue and you want to buy a handful of $400 TeleVue eyepieces. In that case, I say go for it. Either way, have some fun. Looking at the stars is one of the oldest pursuits of humanity and its hard to find a wrong way to go about it.

Unless you’re an astrologer, then you’re wrong