You Should Be Reprocessing Your Data

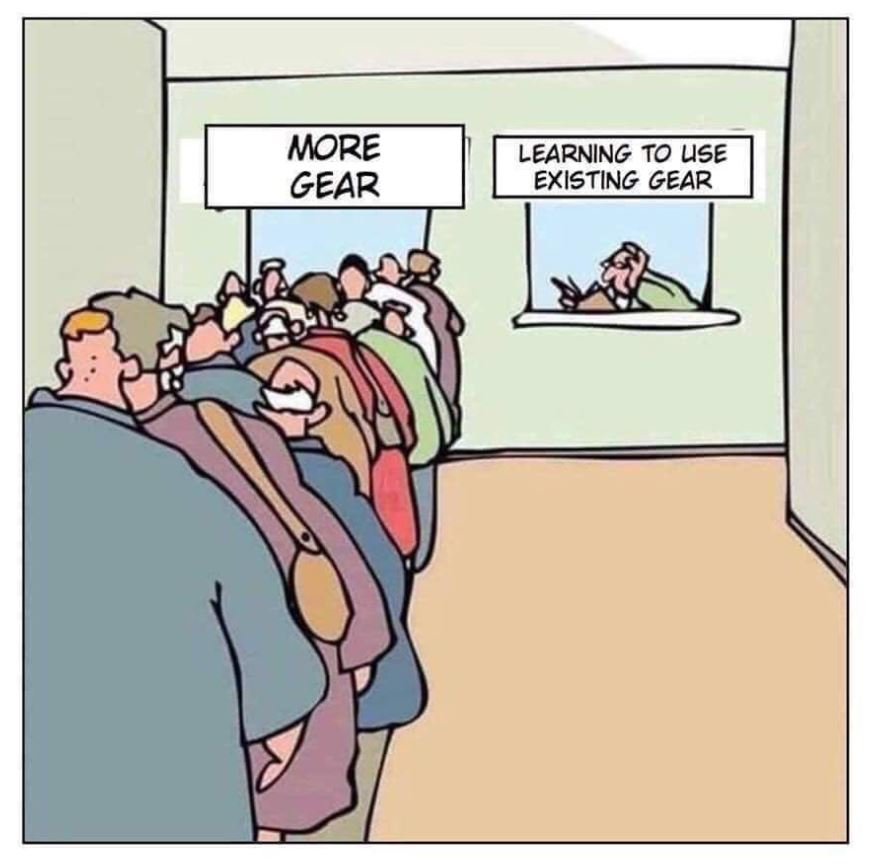

Browse through the posts on almost any community of new astrophotographers and one of the most repeated questions will be “what telescope should I buy?” Significant thought is put into equipment, though you don’t see nearly as many questions on the software involved. There can be a few reasons for this, foremost of which is a human need to find quick solutions. A new astrophotographer on their first outing may spend several hours in the (possibly cold) darkness feeling what I would describe as confused inadequacy only to return home, stack the data, and be disappointed from the result. Given how much of astrophotography can be solved by throwing money at a problem its easy to understand why this is the first impulse. We somehow cling to the idea that “if I buy this telescope / lens then my photos will look better” – all that stands between you and greatness is an online telescope order and a couple days of shipping, right?

Basically

Hard Limits

Coming to this conclusion is understandable since the properties of a telescope and other hardware are physically quantifiable. A telescope has a known focal length and aperture, a given sensor has a verified efficiency across the visible spectrum, and most of the night sky objects we shoot are of (generally) known sizes and magnitudes (“brightness”) - in other words, most ends of the process have edges we can describe in physical terms. The problem is that grey area in the middle involving software editing which can be the biggest hurdle in actually producing a good image - and you can’t really buy that. To add to the comparison above, not only do telescope have quantifiable properties, but also quantifiable limits. Resolution is a good example; according to equations describing resolving power of optics, a 125mm / 5in diameter telescope is physically incapable of resolving detail smaller than 1 arcsecond - one of the many reasons we so often repeat that “aperture is king.” Software, in contrast, is usually proportional in results to the skill of its user (as least assuming you have taken photos of good quality) or is otherwise more fluid in capability as compared to the hard limits of a given optic or camera.

Both is best

Still, learning to edit photos is commensurate to taking them. A newbie astrophotographer is unlikely to know how to operate their equipment or software at the edges of its capabilities; time and experience are required to optimize both. As I said in Astrophotography on a Budget, your first photos will probably be noisy, underexposed, maybe poorly tracked (if you even have a tracking mount yet) – and no amount of software editing is going to fix that. In simpler terms, astrophotography is “a garbage in, garbage out” process. Photoshop or other editing programs will not fix poor data quality, so there is only so much (useful) editing to be done on an image which was noisy, out of focus, or poorly tracked. However, as the quality of the captured images goes up processing the photo can become easier, or at least the improvements become smoother and more noticeable (or in some ways, less noticeable - because when you do things right, people won't be sure you've done anything at all). Sometimes this is done through better use of current gear, and other times it could be through hardware upgrades.

Your first attempt may produce images which feature stars inexplicably drifting - solved by taking more time with polar alignment or by adding an autoguider. Close examination of your shots the next morning reveals that the stars were slightly out of focus - solved by using digital zoom (either on the camera or through a laptop) on a bright star and taking more time with focus, or perhaps adding a Bahtinov Mask (remember to take it off when you’re done!). As your exposure times increases you may notice light pollution gradients become more prominent and learn how to remove them through a software tool like GradientXTerminator or use a Light Pollution Filter (in some cases). The noise left in your stacked photo will drop dramatically as you are able to gather larger and larger exposure totals, and now the noise reduction applied to it will produce smoother result - something which you may only achieve through use of autoguiding. Finally, as the overall complexity of your equipment increases (such as adding Narrowband filters or motorized focusers), the more processing knowledge is needed to effectively combine this data together for the best result of color and contrast, but acquiring this data may actually become easier (or to rephrase, you can sleep a lot more and micromanage your equipment a lot less). Each problem you encounter while shooting or processing could have multiple solutions - some using money, some using time, and some using cleverness.

The First & Last photo I took using a Canon T3i through an AT72ED Doublet Refractor

Still, the unfortunate fact is that cheaper equipment, which is usually found in the backyards of novice astrophotographers, will often have more flaws which require tedious processing to correct. Using a cheap 18-55mm kit lens to attempt a widefield Milky Way shot can work, but many will have difficulty maintaining focus over even short periods of time. If your tracker is overloaded or easily affected by wind the resulting image could have elongated stars. That 70mm doublet you found for $300 may have looked like a good deal at the time, but the slightly-tilted field flattener will mean your corner stars are probably going to need some special attention. Taking reliably good images can be inherently expensive, and that means the budget-minded astrophotographer (which is most of us) is going to be fighting uphill until they both learn their way around the software and can hopefully obtain better hardware. If there is a silver lining here, it is that the difficult experiences in trudging through poor data often means you are better equipped to handle better data as you upgrade your equipment.

Progress on the Orion Nebula using improved hardware - and processing skills - over time

Think Back

Anyway, if you’re a year or two into this hobby or more, hopefully you’ve kept all your old images? If not, you should start. Data storage is getting cheaper by the day and most of my old image projects are barely a couple Gigabytes in total (including calibration frames), so start making backups. Unless you were already quite familiar with photo editing your first attempts at photo processing were probably poor, regardless of how good the photos themselves were. If you keep older photo stacks you can often churn out a better image years after actually taking it. Even today, knowing a lot more about using Photoshop (and now PixInsight) than I did in 2016, if I see that my photo appears substandard to my expectations – and if I am unable to “fix” it – my motto is usually “the data is there, but I’m not good enough to find it yet.” Astrophotography always requires some level of patience and rarely produces instant results. Second to this is occasional blind faith (albeit faith which soon becomes grounded in past experience) that the fraction of the total you see in each individual, noisy image (which may not even have any visible nebulosity) will add up to a pleasing result, and this is especially true when operating under the hope that a “future you” will be more skilled than the “present you” currently reading this sentence.

Finding better software tools can increase this ceiling as well. Photoshop is great for photo editing – but could still be limiting, depending on your needs. Other options include PixInsight, Sequator, SiriL, Star Tools (which I used to use as well), and more. Being familiar with multiple software suites is never bad for improving your processing skills and the addition of experience over time is often the only requirement to turn a decent photo into an incredible one (See the Software Section on my FAQ page for links to the aforementioned programs).

This is also a way to keep busy if your part of the world has extended periods of unusable skies – whether it be from monsoon season or if you find yourself in a period of life where you don’t have the time or ability to shoot anything new. Lacking any ability to capture new images for any reason, you can always revisit old ones.

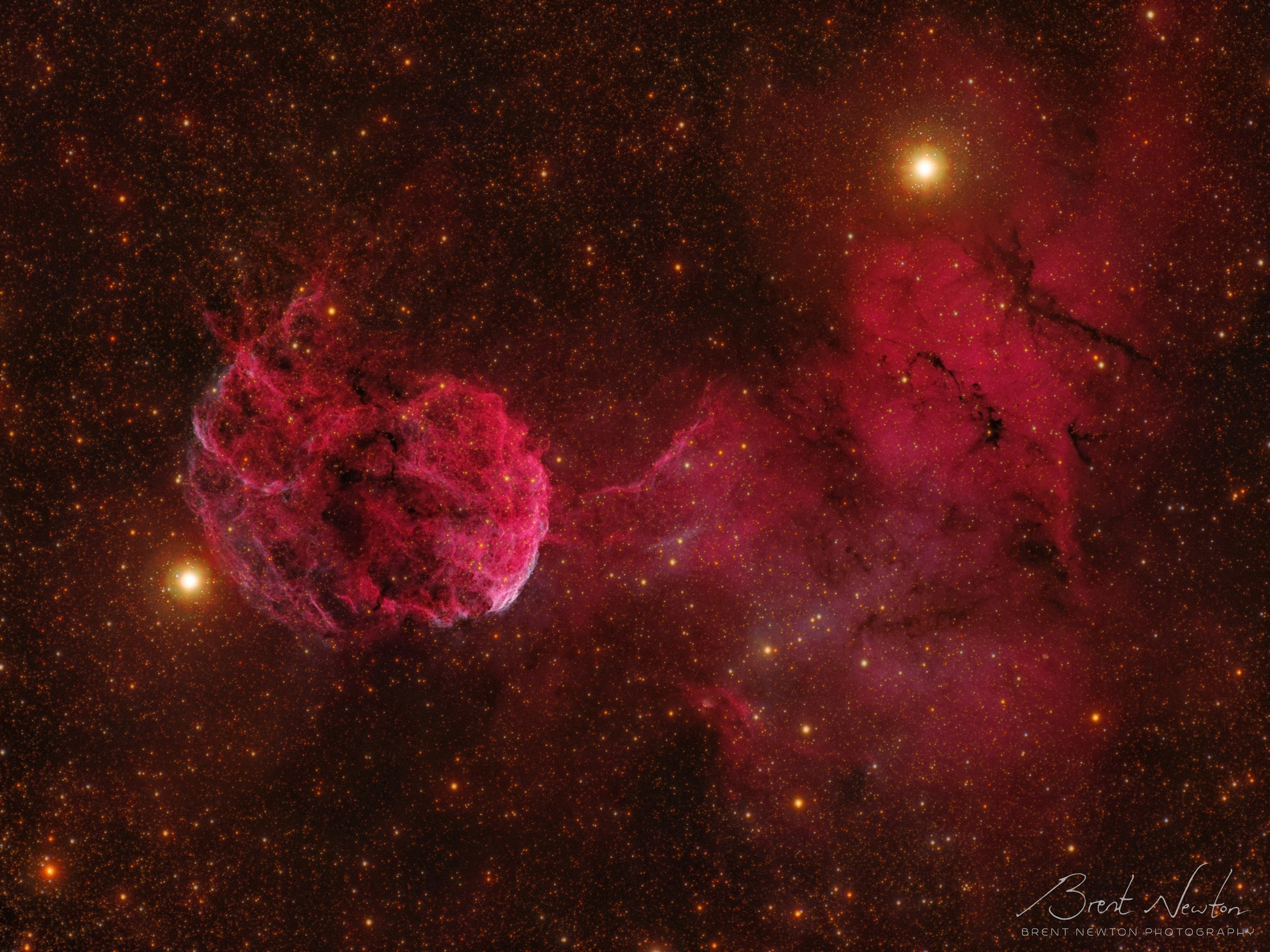

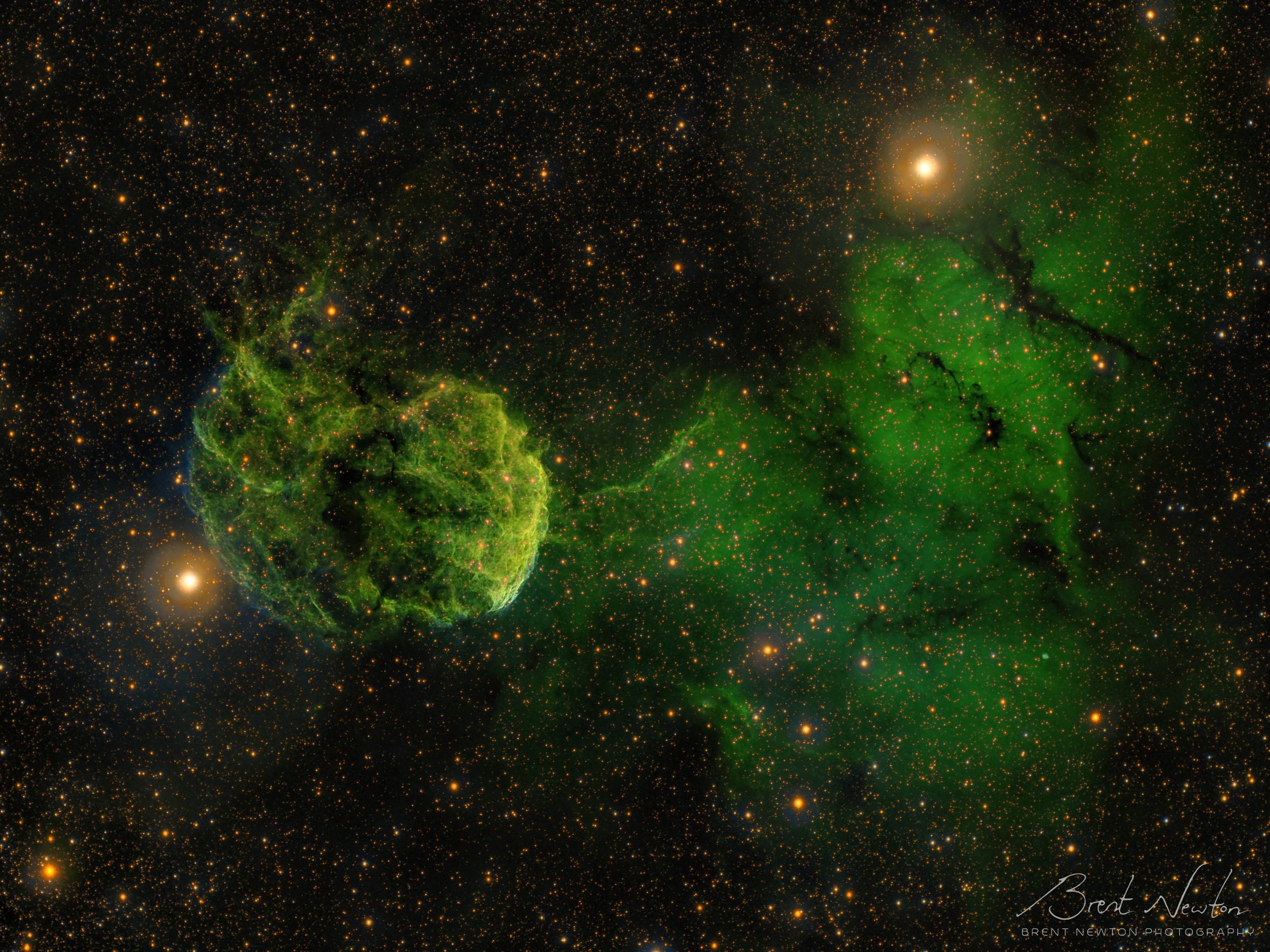

The Shark Nebula (LDN 1235) shot in 2019 and edited both times in PixInsight - the only difference here was me

Ehance the old Photo with New Data

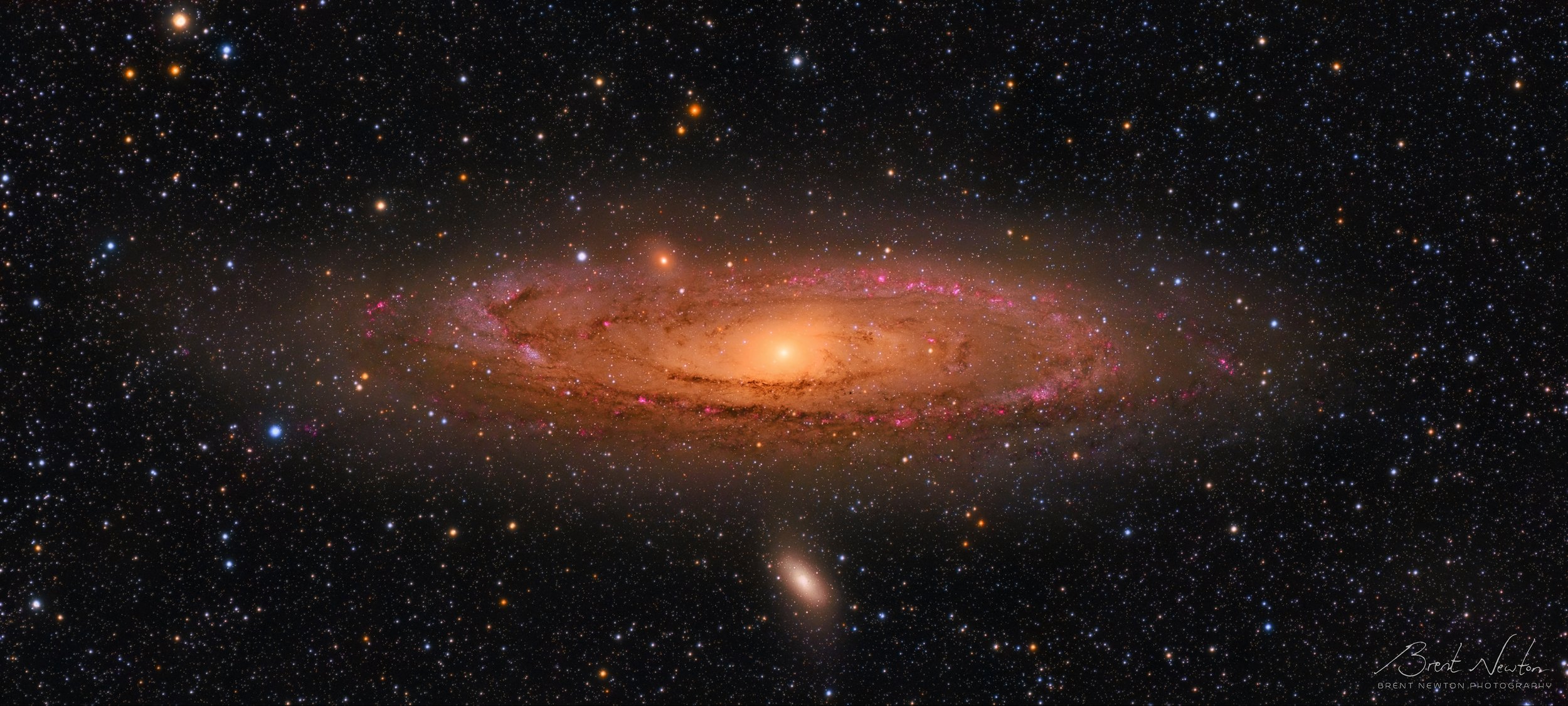

The cool part about space is that it doesn’t care about you at all and human lifetimes don’t even register as a blip in the uncaring and infinite cosmic void. To mildly rephrase, the nebula we photograph basically don’t move at all (there are a few exceptions), so you can keep coming back to the same objects year after year and add more data to their total. As an example, in July of 2016 I spent 2 nights photographing a summer target called the Lagoon nebula. I was using an old Canon 450D/XSi at the time and while this is a capable enough camera it was (and is) showing its age. The resulting image was processed to a reasonable quality for my experience at the time, but I mostly forgot about it as I moved onto another new shot the next month.

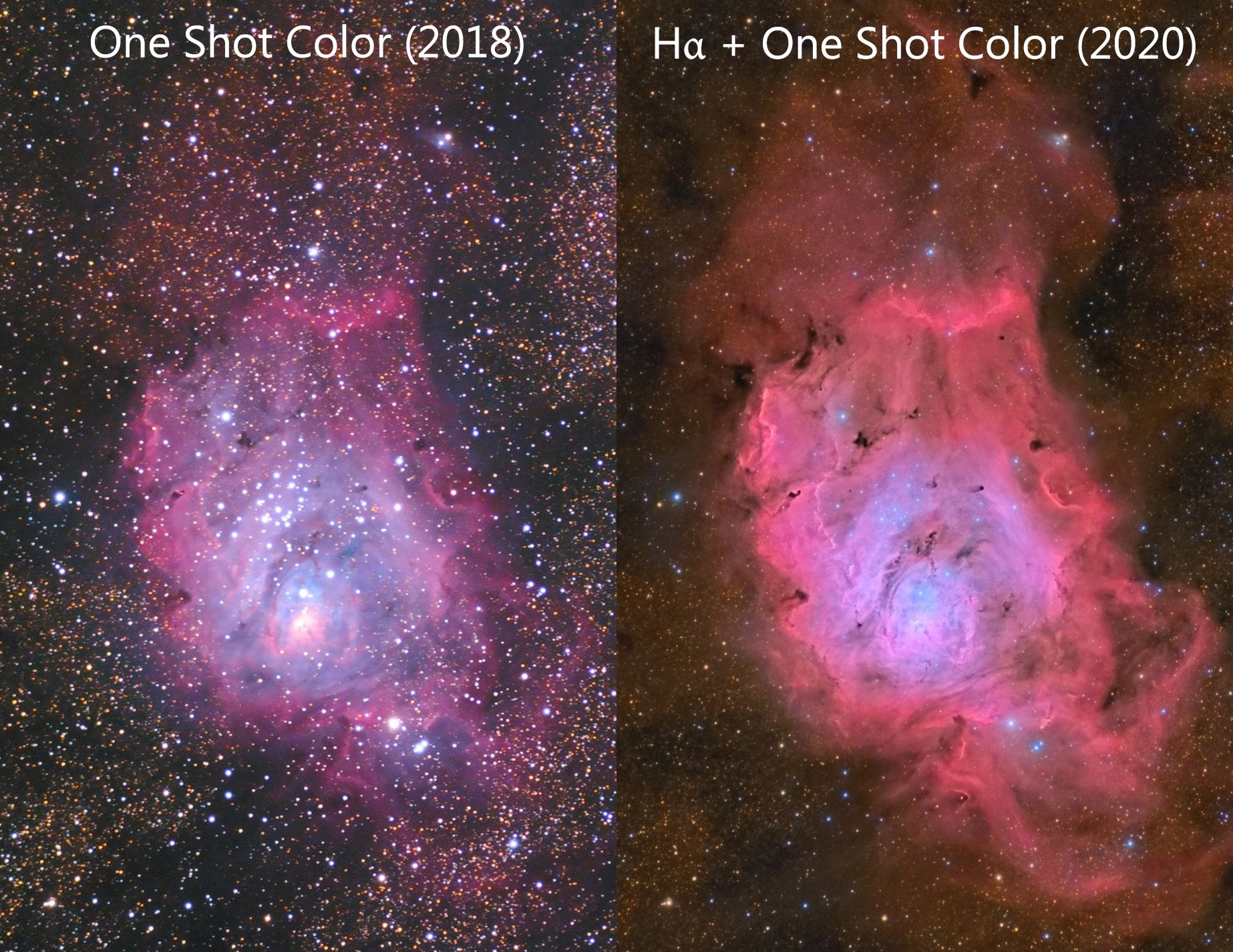

Fast forward to Summer of 2020 and I needed to test some features on my new monochrome camera and narrowband filters but only had a couple hours before the forecasts indicated the sky would cloud over. The Lagoon was well placed in the sky and I remembered that star party from a couple years back. As the 2016 photos contained decent color all I really needed to improve the original was better contrast from my new 7nm Hydrogen-Alpha filter. My additional 3 years of experience would improve the image regardless but now I had even better data which improved both color and contrast.

The difference between these two is only 1.25 hours of additional Hydrogen data

Astrophotography can be exciting – there is a small thrill in that first long exposure flashing up on the camera or laptop screen, especially when in pursuit of a particularly challenging night sky object. Yet it is also a practice of patience; knowing and often assuming that the images taken today could be part of a larger yet unknown image tomorrow.

Scientific Study

Your photos may have other uses as well - did the stack of images you took on an obscure night in February of 2015 have an undiscovered asteroid or comet floating through the field of view? How will you know unless you look? You can “wash” your imagery through a number of programs to search for transient objects like asteroids and comets or even purpose your current equipment in hunting them. PixInsight has a process called ‘Blink’ which makes this easy, and identifying any moving objects found in your long exposures can be accomplished by consulting the IAU Micro Planet Center. Be sure to download their latest Asteroid Database for reference.

Even high speed video capture of the planets and our Moon can reveal interesting events, albeit rarely. The impact of asteroids on the surface or atmosphere of other planets will cause a brief but bright flash. One such event was captured by Ethan Chappel in 2019. He happened to be capturing video data on Jupiter when a ~450 ton asteroid exploded in Jupiter’s upper atmosphere. He did not initially see it, but running his video capture through the software DeTeCt quickly found a bright spot which appeared for 1.5 seconds. A half-dozen other events have been captured in past years, including a bright flash of a roughly golfball-sized rock impacting the Moon right in the middle of a Lunar Eclipse the preceding January. If you’ve deleted most of your planetary video captures I can’t blame you though, an evening of shooting planets (or Lunar mosaics) may generate nearly a Terabyte of data in some cases, so I usually only store the stacked and final image, but it may be worth checking them for these characteristic flashes before deleting them.

A Personal Note

As I write this in late 2022 I am nearing one year since I shot any new data at all. Schooling has been keeping me away from my equipment for most of this year but it didn’t stop me from accessing my older projects. As such, I’ve spent much of my limited free time going back through these older projects and I think the results show significant improvement over the original attempts. When I shot these projects I was much less experienced in the use of PixInsight and my use of the editing tools was much more blunt and lacking in subtlety or restraint - the latter of which can be an especially important quality to avoid unnatural appearances in any final image. I also understand a little more about the physical processes which produce the colors we see in space. Producing “true” color astrophotos is not an attainable goal in some respects, but knowing more about the physics behind it all has prompted me to apply narrowband data to color in more nuanced way, and a way which I think improves the aesthetic of the result.

And on a brighter note, I have had time to consider new equipment upgrades during my break from shooting and have an assortment of new cameras, lenses, and other upgrades waiting for me for when I soon return. Because although I have spent much time here advocating that revisiting older data with the benefit of more processing experience can lead to incredible results, there is little reason to avoid new and better hardware - especially if tempered experience has access to sufficient funding.

All Reprocessed Data